The year starts in November (or sometimes in December)

This series now moves on into the second main section: what I am calling the firmware. This is the way in which we organise and develop our actual practice of reading. I begin with the church year.

We have a range of different years we organise our life by, and they all start at different times. The school year in September, the tax year in April, the calendar year in January. Historically it’s moved around a bit. So it’s not really at all out of the ordinary that the church year begins four Sundays before Christmas, a date that usually falls at the end of November, and sometimes at the start of December.

The pattern of readings followed in Christian liturgy is tied to this year, so that a new cycle of readings begins on the first of the four Sundays before Christmas, called Advent Sunday, from a Latin word meaning “arrival”. The year begins with preparations for the arrival of Jesus.

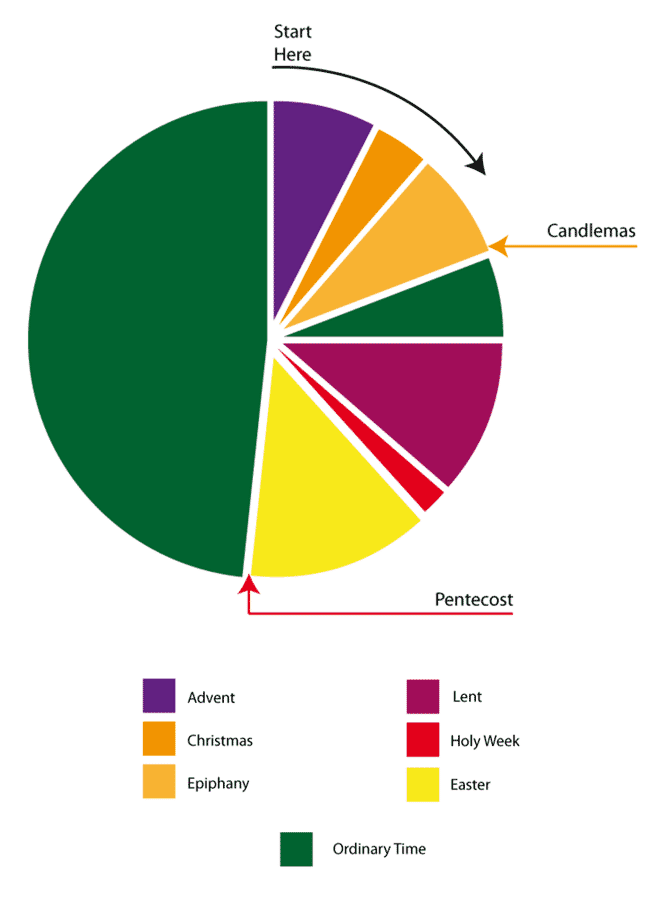

There are different ways of conceptualising the year. Both the diagrams below illustrate the pattern Anglican Common Worship presently follows, with a season of Epiphany (a recent – and in my view unhelpful – innovation). A very common illustration of the year is as a wheel. (Don’t worry too much about the details for now. We’ll come back to these diagrams in due course.)

|

| The liturgical calendar as a single cycle |

On the whole, though, I prefer to think of the year as two key narrative cycles of seasons, one pivoting round Christmas and one round Easter. That’s partly because there is no logical story progression between the two. Some years, when Easter is very early, it seems like we’ve jumped from the beginning to the end of Jesus’ earthly life with scarcely a pause to take breath.

That’s why I tend to prefer the model of two seasonal cycles, floating in a sea of non-seasonal or ordinary time.

Two seasonal cycles swimming in a sea of Ordinary Time |

In this diagram I’ve added the calendar of holy days – commemorations of saints and the like, as an outside twelve month cycle that conventionally follows the calendar year, as it’s organised by date. For those who like to learn specialist or technical terms, the calendar of seasonal time is known as the temporale (from the Latin for “time”) and the calendar of holy days as the sanctorale (from the Latin for “saint”).

That, in short, is the calendar which forms the basis for organising the public reading of scripture. In the next four posts, I will explore it more fully, looking at the Christmas cycle, the Easter cycle, Ordinary Time, and the calendar of saints.

Comments

Post a Comment