When time is ordinary

I should probably offer a health warning on this post: there’s no way of explaining the diversity of ways churches name and number the different Sundays of the year without getting a little bit geeky. I have tried to be as clear as possible, but there is a lot of rather messy detail that demands a certain amount of anorak wearing.

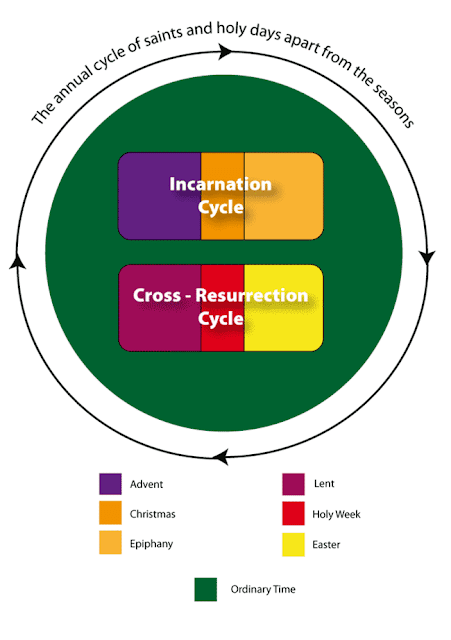

When I looked at the Christmas and Easter cycles, I described them as swimming in a sea of Ordinary Time. Having told these stories, one of the events around Christ’s birth, the other of events around his death, there’s still well over half a year left over. So having told these stories, the church then reflects for the rest of the year on what it means to live out a life that is faithful to the stories of this Jesus, reading through the main teaching sections of the gospels.

These reflections – on what faithfulness to the stories of Jesus looks like – begin with our idea of God. The first Sunday in Ordinary Time is always kept as the Feast of the Most Holy Trinity. It emphasises how telling the story of Jesus has changed the understandings of God the early church inherited from Jewish and Greek traditions of faith and philosophy. Christians have come to understand the one God as the one who is also present in human history in Jesus of Nazareth, and present in God’s church through the Spirit.

There are two different naming conventions used for these Sundays of the year. I begin with the Roman Catholic one, since that lectionary forms the basis for the others. In the Roman Catholic Lectionary for Mass, those Sundays which are not in either the Christmas or Easter cycles are simply labelled Sundays in Ordinary Time. They are numbered in sequence and the numbering begins after Epiphany. The same numbering system is used for the weeks of the year outside the main seasons.

There are a few practical issues that puzzle many people. The first Sunday after Epiphany is usually kept as the Baptism of the Lord. That means that while the weekdays between the Epiphany and the Feast of the Baptism are kept as the first week of Ordinary Time, the Sunday after the Baptism of Jesus is normally the 2nd Sunday of Ordinary Time, or the 2nd Sunday of the Year. The calendar then hits the pause button for Sundays in Ordinary Time on the final Sunday before the start of Lent, and resumes the sequence of numbered Sundays and weeks after Pentecost.

But there’s another wrinkle to catch the unwary out. This second sequence is worked out backwards starting from the final, or 34th week of the year. As a result, very often a week goes missing between the end of the first period of Ordinary Time on Shrove Tuesday, and its resumption on the Monday after Pentecost. For example, in 2020, the last day before Lent is the Tuesday of week 7, and the week after Pentecost is week 9.

If all this calendrical geekiness is getting to be too much for you, then, as the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy reminds us: Don’t Panic. On the whole most people don’t need to know how these dates are worked out. You only need to know which Sunday it is, and between church websites and parish bulletins or newsletters, that’s always easy to discover.

Things are somewhat different with the Revised Common Lectionary. It keeps the idea of Ordinary Time, but has no corresponding weekday lectionary to count weeks of the year. (The Church of England adapts the Roman Catholic lectionary as its weekday lectionary for the Eucharist, and uses the same method for counting weeks of the year. However it goes its own way on Sundays.)

In the ecumenical base pattern, the Sundays between Epiphany and Lent are named Sundays after Epiphany. (I don’t know if this is particularly widespread in any Protestant church in the UK). The Sundays between Pentecost and Advent are left up to local choice for their naming, and are allocated the readings, as in the Roman Catholic Church, working backwards from the end of the year. In the table of readings, Sundays are simply designated as falling between two calendar dates, e.g. the Sunday between June 26th and July 2nd inclusive, Ordinary Sunday 13. This means that despite the different naming conventions, most Sundays people read the same readings whatever they call the Sunday.

In the Church of England, which also broadly follows this practice, books of readings (also called lectionaries) give names to each set of Ordinary Time readings, but not to the Sundays. So for the Sunday just mentioned, the printed lectionary books call this “Proper 8” and say it should be used on the Sunday between June 26th and July 2nd inclusive. The reason for the lack of name is that in any particular year, the Sunday may have a different name.1

This brings us back to one of the ways in which the Church of England differs from everyone else. I noted earlier that Common Worship, building on an earlier experiment, tries to create a season of Epiphany. This means that there are very few Sundays in Ordinary Time between Epiphany and Lent. This even more noticeable since the Church of England not only follows the Revised Common Lectionary option of giving the Sunday before Lent readings themed on the Transfiguration, but also gives the preceding Sunday a set of readings on the theme of creation.

Common Worship also chooses to avoid naming Sundays as being in Ordinary Time, and relates them entirely to seasons or days. Obviously the Sundays of January are assigned to the newly-invented Epiphany season. The Sundays between Candlemas and Lent are named as Sundays before Lent. Those after the Feast of the Most Holy Trinity, in a partial retrieval of the Book of Common Prayer tradition, are labelled Sundays after Trinity, until we reach All Saints’ Day at the beginning of November. Then the remaining Sundays are named as Sundays before Advent.2

To my mind, this rather obscures the concept of Ordinary Time, and, owing much to the traditions of the Book of Common Prayer, you will often hear Anglicans referring to a so-called “Trinity Season”. (That includes some clergy, who really ought to know better.) Trinity is not a season, it’s a historical naming convention. In my view, Anglicans could, and perhaps should, make rather more of the concept of Ordinary Time, and allow the two great seasonal cycles to stand out more clearly in the year.3

Notes

For example, in 2020, Proper 8 (Year A) is used on the 3rd Sunday after Trinity. In 2019 Proper 8 (Year C) was used on the 2nd Sunday after Trinity. This slippage happens because of the way the date of Easter moves around rather than being a fixed point.

This began with an attempt towards the end of the 20th century to create yet another season, paralleling the invention of an Epiphany Season – and end of year “Kingdom Season”. By the time Common Worship arrived, this abortive attempt to create a Kingdom Season had been rejected. I suspect that if Common Worship had arrived a few years later, the Epiphany Season would have gone the same way. The church sometimes has to suffer the fashions and fads of liturgists in the hope it will be good for the soul.

If you wonder whether something is a season or not, there is always a clue in the Sunday’s name in both the Revised Common Lectionary and Common Worship. If it is in seasonal time the Sunday is named as a Sunday in (e.g.) Lent, or of (e.g.) Easter. If it is in Ordinary Time, it is named either 2nd Sunday before (e.g.) Lent or after (e.g.) Trinity. By being explicit about Sundays in Ordinary Time, the Roman Catholic Church avoids this problem.

Comments

Post a Comment