Negotiating the master-slave relationship in a church family: the letter to Philemon

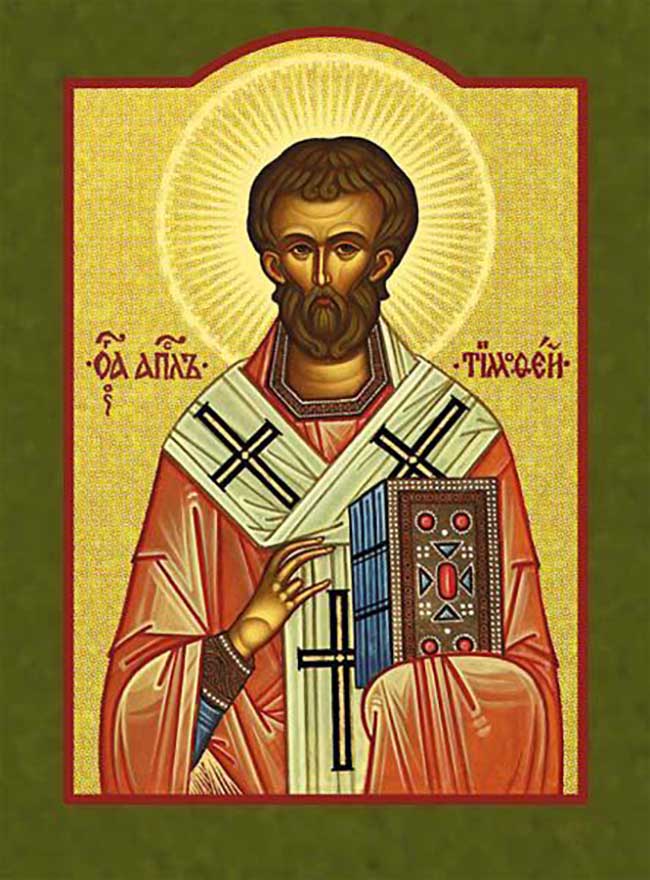

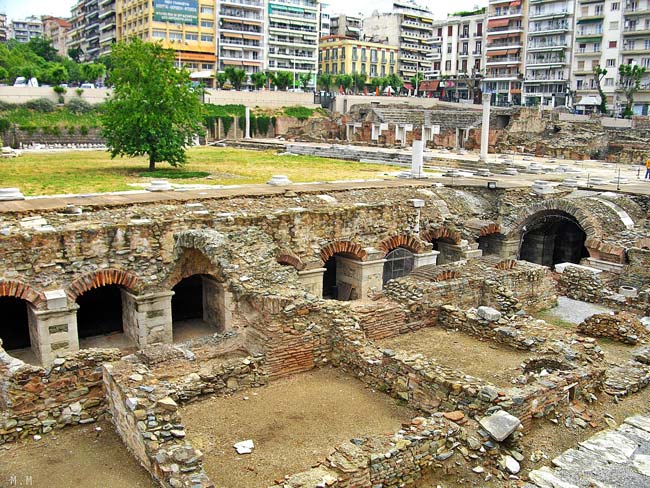

Philemon is the shortest of all Paul’s letters. (That hasn’t stopped someone writing a 600 page commentary on its 25 verses!) In the Roman Catholic lectionary selected verses are read on the 23 rd Sunday of Ordinary Time in Year C. The corresponding Proper 18 in the Revised Common Lectionary, as so often, lengthens the reading to almost the whole letter, leaving out only the closing greetings. While some of the precise details are obscure, the overall picture is generally agreed to be straightforward. Philemon seems to be a member of the church at Colossae, who found his Christian faith through Paul’s ministry. Onesimus is a runaway slave of Philemon who has ended up in Paul’s company, and been visiting him while Paul is under arrest. As a result of his contact with Paul, he has come to faith in Christ independently of the commitment made by his master. Slavery was everywhere in the Roman world. Picture via Wikipedia (public domain) According to their shared cu...