It’s the end of the world as we know it: the Thessalonian letters

I take both the letters to the church at Thessalonica together. Between them they have no more lectionary readings than the individual letters we have already looked at, and they cover much the same territory. Their key theme is how to live when you are expecting the end of the world as you know it. While living in expectation of Christ’s appearing remains a significant theme in Paul’s letters, it is at its most intense here. It also seems to be an expectation that is not fully understood by his Gentile converts in Thessalonica, who lack the grounding in Old Testament texts to fully appreciate it. Unsurprisingly, given this emphasis, the majority of readings from these letters comes in the Advent season.

These letters were (at least if they are both by Paul) probably written fairly closely together. According to Acts, Paul visited Thessalonica early on his second missionary journey (Acts 17), and these letters seem to have been written fairly soon after that, making First Thessalonians perhaps his earliest letter. According to the account in Acts, his exit was a matter of rather hasty necessity in the face of Jewish mob violence: perhaps that explains why he is so anxious about how things have gone on since his departure.

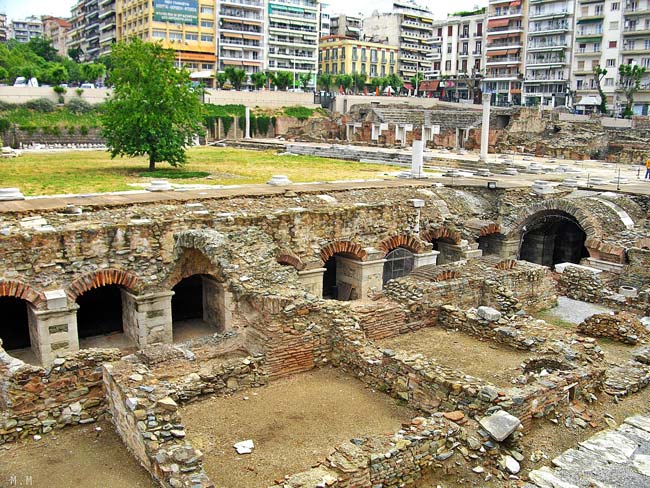

|

| Roman Thessalonica’s forum, with modern Thessaloniki behind it. Via Wikimedia Commons. |

The opening half of First Thessalonians show something of his anxiety that things there went almost too well. Would the Thessalonian Christians persevere in their faith (which in characteristically Jewish fashion Paul describes as having “turned to God from idols, to serve a living and true God (1 Thess 1:9),” or return to their previous existence? Paul shows himself unusually apprehensive about the outcome of his ministry. He rehearses his relationship with them, stressing his ethical qualifications as evidence of his care for them. And because he was so anxious that he might have failed, he sent Timothy to them, and is now exultant and thankful, because Timothy has returned with the news that the Thessalonian church is largely a success story.

From the beginning of the letter, Paul has characterised Christian existence as “waiting for God’s Son from heaven”. In the later chapters he encourages them to live as those who at any moment might find Christ arriving, in an image from Jesus’ teaching, “like a thief in the night” (1 Thess 5:2). He uses an earlier version of his imperial metaphor about Christ’s return.1 Just as the emperor or his representative might arrive with an entourage, and people from the city would go out to greet him, so Christ will return to earth accompanied by those saints who have died, and those Christians still living will start to journey into the sky to meet them.

This metaphor only works with a fairly literal model of three tier universe, which is not our model. But Paul is less interested in the mechanics, than in assuring the Thessalonians that those who have died will also – and indeed before those who have not – experience the resurrection. Being raised with Christ did not mean they would not die, but that they were given an inalienable promise of life in Christ’s new age.

Second Thessalonians suggests that Paul has become rather more worried by strange beliefs circulating in Thessalonica about Jesus’ final appearing. He unusually stresses the place of God’s judgment on those who do not acknowledge God (2 Thess 1:8-9). But he appears to have two main concerns. The first is one Jesus warns about in the gospel traditions, that some people will claim Jesus’ appearance is happening when it is not (2 Thess 2, and compare e.g. Matt 24:22-27).

The second concern picks up something only hinted at in his first letter to them: the importance of working and not being idle (1 Thess 4:11-12; 2 Thess 3:7-12). Historically, most Christians seem to have read this as assuming that the Thessalonian expectation of Jesus’ imminent return was so strong, and their timetable for it was so short, that they had simply downed tools, and were not expecting any need to provide for the future.

A more recent view I find attractive is that, as poorer members of the church had been given access to a new network of patrons, they were putting their energy into promoting their new patrons’ business in return for the basics of living.2 Either way, Paul expects his Christians to get on with the business of living out their faith in the real world, in a way that may also allow them to contribute to the needs of others as well as support themselves.

Notes

See my earlier post on Philippians.

- As far as I am aware, a version of this view was first put forward by Bruce Winter “‘if a man does not wish to work…’, a cultural and historical setting for 2 Thessalonians 3:6-16” Tyndale Bulletin 40.2 (1989) pp 303-315

Comments

Post a Comment