Arguing over the Old Testament

If you were surprised it took a few centuries (as the previous post described) to reach agreement about the contents list of the New Testament, you may be even more surprised by the length of time it has taken for the Old Testament. Christians have never produced a fully-agreed contents list for the Old Testament. Roman Catholics, Orthodox Christians, Anglicans and Protestants disagree about which Old Testament books they should read in public.

The seeds of this disagreement lie in the distant past. The early Christians essentially used the books which were in circulation among the synagogues of the diaspora:1 the Greek-speaking world of the ancient Mediterranean. Greek in the ancient world functioned much like English in today’s world: it was the “global” language of the Graeco-Roman world. The earliest books of the bible to be translated into Greek were the books of Torah: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The other books followed, with pride of place going the prophets2, and then the remainder.

Some of these “other books” were translations of Hebrew books which were simply much more popular among Greek speakers, and some were written for the first time in Greek. This meant that in practice, Jews living in the diaspora were probably acquainted with a wider range of books than those who never left Roman Palestine.

The early Christians, increasingly living all over the Mediterranean, and losing touch with many aspects of their Jewish background and heritage, simply borrowed Jewish collections of books and made them their own. Christian use of these books, together with the way in which the early rabbinic movement started to rebuild Judaism after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem, meant that the synagogues started to reject them. Increasingly Judaism retreated to the core Hebrew books, and abandoned these Greek books to the churches.

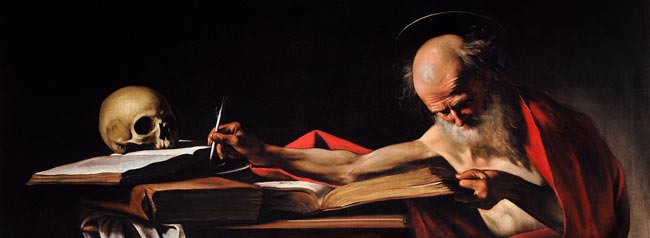

|

| Detail from Caravaggio’s St Jerome Writing (public domain) |

Disagreement over these books flared up most notably when St Jerome began producing an official translation of the bible into Latin, in the last decades of the fourth century, and into the early fifth century. Latin had overtaken Greek as the common tongue of the Western Mediterranean (though Greek remained the language of the East), and a reliable authorised translation was needed. Jerome’s work became the basis of the Vulgate, which in turn became the primary bible of the Roman Catholic Church. A revised version still serves as a significant version for Catholics to reference in preparing translations into other languages.3

In preparing his translation, St Jerome became aware that sometimes the Hebrew and Greek texts were different, and sometimes the book didn’t exist in Hebrew at all. For example, the Hebrew text of Jeremiah is considerably longer than the Greek text, and the Hebrew text of Daniel is quite a bit shorter than the Greek text.4 The Wisdom of Solomon, which influenced early Christian thinking about Christ as the word of the Father, didn’t exist in Hebrew at all.

Jerome wanted to argue that Christians should use the same collection as Jews did, which was not a particularly popular argument. Jerome liked arguments, and made enemies easily, which didn’t help his cause. Moreover, Christianity already had a well-developed anti-Semitic streak (much to its shame) which certainly affected the argument as well. However, most churches had already become quite attached to some of these books, and didn’t want to lose them from their collections of scriptures. One in particular, the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sirach, was so popular it became known, despite its Jewish authorship, as Ecclesiasticus – meaning essentially, the church’s book.

After Jerome’s time, the argument was largely forgotten and the church went on reading these additional books, in Greek in the East, and in Latin in the West. It flared up again in spectacular style at the time of the Reformation in the 16th century.5

Part of the background to this was the preceding century, a period known as the Renaissance, when a new form of scholarship emerged out of the mediaeval universities. This put a high premium on returning to the sources: the great texts and traditions of ancient Greece and Rome. The Renaissance expanded into rediscovering the Greek text of the New Testament, and the Hebrew text of the Old. Some of the differences between these versions, and the Latin translation began by Jerome some 1100 years earlier became apparent.

Those who were arguing for wide-ranging reform of the church seized on the rediscovered Greek and Hebrew and began arguing for a revised bible along the same lines that Jerome had wanted to see, leaving out the books that were used in the church, but not in the synagogue. Like the rest of the church, the bible ended up getting split along partisan, denominational lines. Most Protestants ended up rejecting these books altogether. The Roman Catholic church ended up with its first officially authoritative statement that they were proper scripture alongside the other books.6

The Anglican church ended up somewhere in the middle, quoting St Jerome. It would read these books in public worship as a guide to life, but it wouldn’t use them to prove any particular doctrinal point was true.7 It then collected them together in a separate section of its own, called Apocrypha – a rather misleading name, as the word really means hidden. Far from being hidden they were indexed, placed either between the Old and New Testaments, or after the end of the New, and read in the late autumn at Morning and Evening Prayer on weekdays.

Notes

A Greek word meaning “dispersion” or “scattering”. Then, as now, more Jewish people lived outside the borders of Israel / Palestine, than lived within them. Today the word can mean any migrant population living around the world, but originally just referred to the Jewish population scattered around the world, in places as far flung as Babylon, Ethiopia and Spain.

In Jewish tradition, “The Prophets” includes a rather different collection of books from those Christian tradition thinks of as prophets. I’ll discuss this in a future post in the “software” section.

The current Vatican instruction says: “in the preparation of … translations for liturgical use, the Nova Vulgata Editio, promulgated by the Apostolic See, is normally to be consulted as an auxiliary tool, in a manner described elsewhere in this Instruction, in order to maintain the tradition of interpretation that is proper to the Latin Liturgy.” (Liturgicam Authenticam 24)

A Hebrew version of Jeremiah much like the Greek translation eventually turned up among the Dead Sea Scrolls. It is about a fifth shorter than the version underlying our Old Testament book today. Daniel included several additional sections, a prayer and two stories, in the Greek text. Clearly some books existed in more than one edition. Wisdom was originally written in Greek, perhaps a few decades before the time of Jesus.

This is the time when, following the protests of Martin Luther in 1517, a number of different theologians and politicians argued for major reform in the church. Technically, it was not one reformation but many. Lutheran, Calvinist, and Catholic Reformations (to name but three) went on alongside each other over the course of the 16th century. The end result was a series of major splits in the Western Church, the beginnings of the various denominations we see in today’s church.

The Roman Catholic church therefore refers to them officially as deuterocanonical. “Deutero” means second: they were recognised as scripture second or later after the other books had been recognised. In this blog I shall normally use this language, as there are many other ancient books classified as Apocrypha, to which no mainstream Christian group accords any scriptural status.

We will return to the reading of these books in public in later blog posts. The official Anglican position is set out in article 6, of its 39 articles of religion: “And the other Books (as Hierome saith) the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine” (Heirome is an early English spelling of Jerome.) The articles are available online.

Comments

Post a Comment