Writing and reading

The books that go to make up the bible were written for reading aloud. This is generally true of books in the ancient world. There’s a story from St Augustine that underlines this point. He was a North African bishop in the late fourth and early fifth century, who was also one of the cleverest and well-educated men of his day. In his Confessions he thinks it worthy of comment that, Ambrose, bishop of Milan, always read silently. Reading aloud was the norm, even for the highly educated who read on their own.1

For most people, in a society where the majority could not read, the only way they encountered books at all, was through other people reading to them or for them. There are places where, in different ways, that practice shows through in the pages of the bible.

Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians is commonly believed by scholars to be the first book of the New Testament to have been written, sometime around the year AD 50. As he comes to an end, Paul says: "Greet all the brothers and sisters with a holy kiss. I solemnly command you by the Lord that this letter be read to all of them. The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you." (1 Thess 5:26-28)Paul has written to and for “all the brothers and sisters” (his language for church members) and he wants them to hear his own words, not just a summary. It seems reasonable to deduce that he knows there is at least one person in the congregation in Thessalonica (modern Thessaloniki) who can read, but that many – most, if not nearly all – can’t.

Those who read the same books today in church settings are standing in a long line of people who are using them as they were originally intended to be used. They are texts written to be performed.

Today’s readers have some advantages over the readers of Paul’s day. First, they get to read a printed text, rather than a handwritten one. If I’d written this book, rather than typed it, dear reader, you wouldn’t have a chance; my handwriting is dreadful. All the books written in the first 1500 years of the church’s life were handwritten, and almost certainly not by the people we call their authors.

We tend to think of learning a single skill: reading-and-writing. It was not so in the past. Quite a few people who could read well – including the very highly educated – might only occasionally have bothered with the physical activity of writing. Writing was a different job, usually carried out by commercial writers or slaves. We meet some of the members of this group of specialist writers in the pages of the gospels as the “scribes” who sometimes dispute with Jesus. And we can see it operating in some passing references in Paul’s letters.

At the end of his first letter to the Corinthian church, he remarks: “I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand.” (1 Cor 16:21) The rest of the letter, it seems, has been dictated to a proper writer. In another letter, Galatians, Paul appears at one point (at least) to take over the writing. It’s a letter in which he is especially emotional, so that probably explains why. He says: “See what large letters I make when I am writing in my own hand!” (Gal 6:11) Trained scribes learnt a professional way of writing. Large letters are the mark of an amateur writer, using up rather more of the quite expensive papyrus or parchment than they need to.

If this firm distinction between reading and writing seems strange, perhaps the best analogy is between a touch-typist and someone like me, who uses two (or at best four) fingers to type with. I don’t have the professional skill set, even though I think I’m reasonably well educated, and fluent in English.

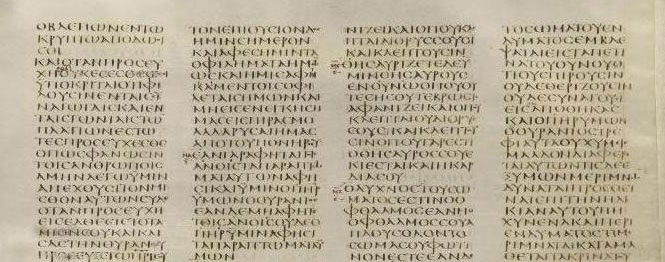

There is a second advantage which readers have today. Our texts have all sorts of help available to the reader. First, we use a mix of upper- and lowercase letters. We start sentences with a capital letter, and also use capitals for names. In the ancient world, they only used capital letters. Then, we use spaces between words, and lots of punctuation. The ancients wrote a stream of continuous characters in capital letters, and the reader had to divide them into words and phrases as they went along. Imagine visiting a website called http://www.godisnowhere.com and working out whether it’s an atheist site (God is nowhere) or a believing one (God is now here). That sort of problem could crop up any time for the ancient reader. We also have other helps, like chapter and verse numbers, and often nowadays paragraph headings. All these have gradually been added over time.

|

| Half a page (of Matthew 6) of Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th century bible with its own website |

Despite all these difficulties, early Christianity was determinedly literary. Christians wrote books, lots of them, and expected other Christians to read them. Those books which ended up getting into the bible were simply the most important to the mainstream of the growing Jesus movement as that mainstream morphed into what became known as orthodox or catholic Christianity. Along the way, the early church popularised the use of books instead of scrolls. In choosing the medium of a book (properly called a codex), the early Christians made an impact on how writings were produced which has lasted to the present day.

The writings we now have in the New Testament are just the tip of the iceberg; the early churches were very keen on making books. They told stories, offered instruction, shared visions and wrote letters. Yet even though the production of books was central to their shared life, most early Christians mainly experienced these books only as they were read aloud when they gathered. For the average church member, the scriptures (like all other literature) were books to listen to. They were not read in solitary quiet times, but in corporate worship and social learning.

Readers were vital to that experience, and those who read the bible today in church inherit a long and honourable tradition that has been at the heart of historic Christianity. Initially it was simply a function. It quickly became valued as a ministry.

Notes

- Augustine's description comes in Confessions 6:3 (e.g. as translated by Henry Chadwick, Oxford World Classics 1991 , p93)

Comments